Spanish Representations of Malintzin

1500s/1600s

Bernal Díaz de Castillo, conquistador and follower of Hernán Cortés

“Doña Marina was a person of great presence [importance] and was obeyed without question by all the Indians of New Spain.”

“After Our Lord God, it was she who caused New Spain to be won.”

Hernán Cortés, Spanish conquistador

“the tongue... the translator... who is an Indian woman of the land."

"The Meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma" Second half of the seventeenth century.

Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma, the Aztec King, meet for the first time on the Shores of Lake Texcoco. Malintzin is depicted in this exchange, next to Cortés.

The cover of The Second Letter of Cortés (written to Emperor Charles V). It is the only place that Cortés mentions Malintzin/doña Marina.

Map of Tenochtitlán from The Second Letter

Díaz's memoir, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, is one of the first texts to not only refer to Marina but also pay special attention to her. Díaz can be pointed to as providing the most comprehensive Spanish historical construction of Marina.

Portrait of Cortés

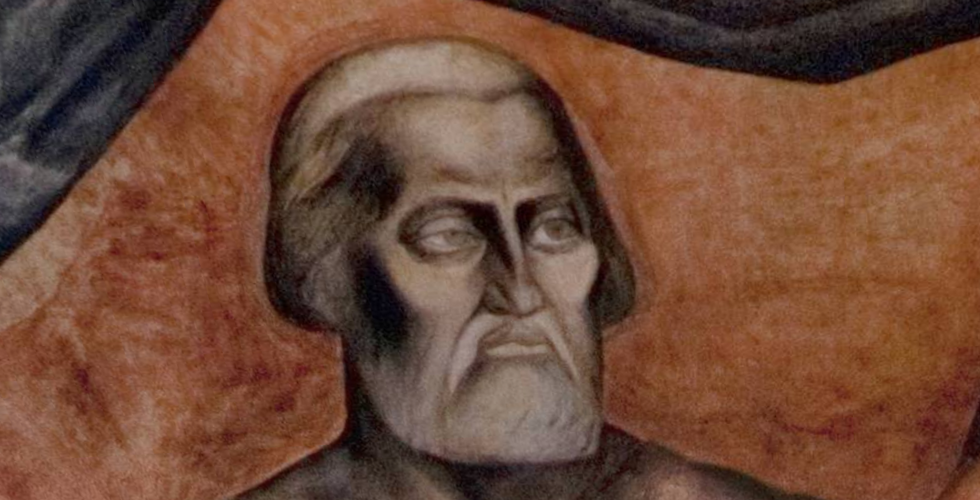

Portrait of Díaz

Indigenous Representations of Malintzin

Malintzin, La Malinche, Doña Marina

1500s

Hover your mouse over an image to learn more, and click the image for a closer look. If applicable, look through the gallery using the navigation arrows.

Mapa de San Antonio Tepetlan, sixteenth century

"Texas Fragment", early sixteenth century

Lienzo de Tlaxcala, mid-sixteenth century

* a useful note from Camille Townsend,

author of Malintzin Choices

"...after the people who had actually known Malintzin had all died, almost no one mentioned her for well over two hundred years. In that period, the image of the indigenous helpmeet was altogether too commonplace to merit notice.

But in the early nineteenth century, when Mexico broke away from Spain, any friend of the Spaniards came to be seen as a dastardly foe. In the anonymous 1826 novel Xiconténcatl, Marina was for the first time suddenly presented as a lustful, conniving traitor. The story had wide appeal in a newly nationalistic setting." (2)

Idea - analyze el sueño de la malinche (after mexican revolution, around ww2)

Ignacio "El Nigromante" Ramírez, journalist, poet, lawyer, politician

On the day of Mexican Independence in 1861: the Mexican people "owed their defeat to Malintzin - Cortés's whore."

Late 1800s

Post-Independence (1821) Nationalist Representations of Malintzin

V. Calero, writer

Describing Malintzin for a Yucatecan literary journal in 1845:

A woman who was "ardent, passionate, impetuous."

Under the tutelage of Spaniard Jerónimo de Aguilar, she was saved from the "defects of her basic education."

Her "charm" was first and foremost the reason why she birthed Cortés's son, Martín, and not Cortés's own actions.

Early 1900s

Post-Revolution

(Male) Artist Representations of Malintzin

"Cortés y La Malinche", by José Clemente Orozco. Mexico City, 1926.

The famed muralist Orozco created this fresco in 1926 in Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City during. It was created at the height of the Mexican muralist movement, and is arguably his most famous public mural. Cortés and Malinche are sitting next to each other, and their skin tones are stark contrasts of white and brown. Cortés looks up and into the distance, his hands and arms in possessive positions regarding Malinche. Malinche looks towards the ground, in a relatively more relaxed and submissive stance. Orozco alludes to the notion that Malinche is the Eve of Mexico, which is also echoed in Octavio Paz's El laberinto de soledad. The corpse of an Indian lies at their feet. Scroll through the gallery for closer looks of the mural, and click here to visit an interactive 360 photograph of the mural.

"El sueño de la Malinche" [The Dream of Malinche], by Antonio Ruiz. Mexico City, 1939.

Antonio Ruiz created this oil painting of Malinche in the international surrealist style. Central to Surrealism was expressing the unconscious and illogical, while paying meticulous attention to realistic detail. Malinche lies asleep on a bed with a Mexican town built on top of her sheets. It evokes the role of female Aztec earth deities, and reflects the idea that Mexico was founded upon the "ground" laid by Malinche's life. She is responsible for this community; if she moves or even awakens, the community will fall. Her positioning on the bed is sensual, alluding to her relationship with Cortés. Is Malinche dreaming of being free from preserving the city? Is she dreaming of how to protect and sustain the community? The concept of survival and gender embedded in this painting intermingle and overlap. Scroll through the gallery for a closer look at parts of this piece.

Late 1900s

Chicana Feminist Representations of Malintzin

In the 1960s and 70s, a generation of Chicana feminists raised their voices against the gender conflicts that they were experiencing as women within the Chicano social protest movement. Although the Chicano movement challenged persistent patterns of inequality in the United States, it ignited a political debate between Chicanas and Chicanos based on the internal gender contradictions prevalent within El Movimiento. Chicana feminists produced an ideological critique of the Chicano movement that fought for justice yet maintained patriarchal structures of domination.

Part of this movement involved a revitalizing and rewriting of Malintzin. In the words of Irma Cantu, Malinche became "a vital, resonant site for Chicana writers through which to respond to androcentric ethno-nationalism and to claim a gendered oppositional identity and history.

"La Malinche", Carmen Tafolla (1967)

Carmen Tafolla's "La Malinche" reclaims Malintzin's history by reworking and reimagining Spanish and Aztec accounts of her role during the conquest. Tafolla makes room for Malinche's agency and vision of her future, imagining Malinche's ethnic identity and nationalist agenda while being conscious of her own positionality in the Chicano movement. Above is Tafolla's reading of her poem, and to the right is the poem in its written form.

The Wounding of the india-Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa

from Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza

"Malinali Tenepat, or Malintzín, has become known as la Chingada--the fucked one... Whore, prostitute, the woman who sold out her people to the Spaniards are epithets Chicanos spit out with contempt."

"The worst kind of betrayal lies in making us believe that the Indian woman in us is the betrayer."

"The spirit of the fire spurs her to fight for her own skin and a piece of ground to stand on, a ground from which to view the world--a perspective, a homeground where she can plumb the rich ancestral roots into her own ample mestiza heart."

Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands/La Frontera is a canonical work of literature in the Chicana feminist movement. In The Wounding of the india-Mestiza, Anzaldua rejects popular mythology about Malintzin, naming the oppressive forces that have victimized Malinche, and noting their self-destructive ends. She reclaims the figure of Malinche, and defines empowerment through Malinche's struggle not only during her lifetime, but in the pain of how she is remembered by Mexico.

A reading and visual slideshow of The Wounding of the india-Mestiza can be found to the left, along with notable quotes at the bottom.